Color Inks and Other Techniques, Pt. 2

In this segment, taken from his 2008 talk at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for his exhibition The Printed Picture, Richard Benson walks us through various printing methods . He gives an overview of rubbings, pantograph etchings, the daguerreotype, and silhouettes. Pictures associated with each of the main themes presented in the segment can be found by clicking on any of the section links below.

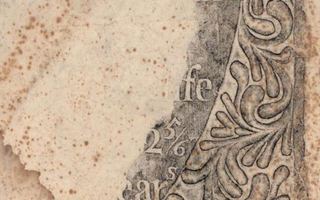

Rubbing. John Stevens. Decorative tombstone border carved in slate. c. 1715. 17 1/2 x 11 1/4” (44.5 x 28.6 cm). Printed by John Howard Benson. c. 1940. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The mechanically derived picture was an age-old pursuit. The ultimate solution was photography, in which light itself formed the image, but long before that medium’s invention there were attempts to somehow make pictures without having to learn to draw. The problem here was to find a physical analog—some structure that mimics the modulations of another—for the object being copied. (For the baby boomers among us the most common analogs used to be the old vinyl records; the wiggles and ups-and-downs of the groove on each side of the record imitated the frequency and intensity levels of the recorded music.) Three-dimensional analogs could be made from the earliest years of civilization, by casting objects: a mold could perfectly imitate the form of the original, and multiple copies could be made easily. The most common of these was and is the building block, cast from a fabricated mold to imitate the carved stone blocks of earlier times. Copying two-dimensional pictures proved to be far more complex. There were many efforts to find pictorial analogs, and this small section describes a few of them.

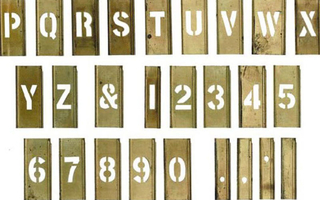

Stencil Letters (see Relief Printing)

Stencil letters. C. H. Hanson Company. Stencil Set, Marking, Lockedge, Adjustable, Brass, 1 inch size. c. 1945. Each 2 1/2” (6.4 cm) high. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A set of marking stencils made for the United States military during World War II.

Stencil has enjoyed a wide application in simple lettering, for packing cases, pedestrian crosswalks, and hundreds of other marking chores. The stencils, often cut out of stiff paper, are held against the support; paint or ink wiped or sprayed across them passes through the areas that have been cut away, leaving the writing behind. The letters we see here are from a set of brass stencils made for the U.S. military during World War II. This alphabet shows the primary design requirement for a stencil: that all interior voids in the letters be connected to the surrounding background. This is necessary because letter parts such as the center of an “O” would fall away in the stencil if not held by small strips to the outside of the letter. The need to hold all the parts together gives stenciled lettering its characteristic look: the letters are simple and read well, but, once printed, have gaps in them to accommodate this structural requirement.

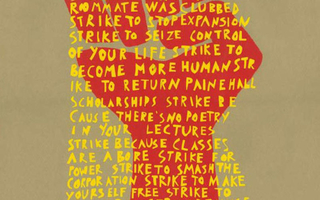

Silk screen print. Strike Poster Workshop, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University. Strike for the Eight Demands. 1969. 20 7/8 x 14 15/16” (53 x 38 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Silkscreen prints are made with stencils held on an open-weave sheet of stretched cloth. Many modern silkscreen prints use photographic stencils, made by applying light-sensitive emulsion to the screen. Silkscreen is the medium of most of today’s decorated T-shirts.

Modern Etching (see Intaglio and Planographic Printing)

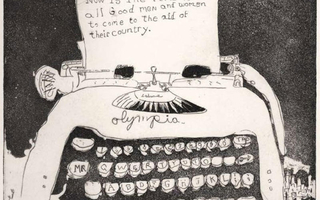

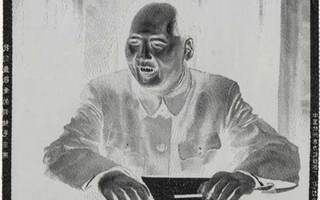

Etching with aquatint. Sam Messer. Typing Exercise #2. 2004. 11 x 10 1/8” (27.9 x 25.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Sam Messer.

Many modern print editions are produced for artists by professional technicians in commercial studios, but this etching with aquatint was made entirely by the artist himself.

This is an etching made by my friend Sam Messer, who teaches at the Yale University School of Art. The print uses linear etching, drawn in the resist with a needle and then chemically etched, but also has large areas of aquatint, creating the darkness in the background and between the typewriter keys. Sam teaches painting and printmaking and after hours goes into the printshop at the School, where students are doing projects, and works alongside them making pictures for himself. Art education is a tough thing to do well and many of us in that trade think this is the best (and perhaps only) really good way to teach: to make your own art along with the students.

So the students come to understand the process as a whole, and can see the complex physical and intellectual activity needed in such work. I don’t raise this subject here to praise Sam, but instead to point out that there are two very different ways in which artists practice printmaking today. The old technologies have survived in schools and privately run workshops, but their technical demands are so intimidating (and dirty) that many artists have chosen to leave that side of the activity to hired professionals. The artist goes to the shop, draws on the plate or stone, and then watches while the skilled technician does the chemical and physical work of producing the print. By engaging in printmaking this way the work can have a physical perfection and slickness not available to most artists who might do the work themselves. But working this way also tends—I believe—to sterilize the work, eliminating all those delights that occur when the holder of the artistic vision skates close to the edge of physical disaster while driving a recalcitrant medium in unexpected directions. Artistic printmaking is a big business; successful artists working with professional ateliers can generate large incomes for themselves and their marketers. The work will be technically perfect—appropriate for a grand living room wall—and will spread the artist’s work far and wide, making multiple copies available at a modest cost compared to that of an original painting. Whatever we think of this practice, it is one of the primary engines that preserves the old technologies long after they have outlived their original uses. Even so, those atelier-produced prints are the antithesis of ones derived entirely from the hand of the artist himself.

Weaving (see Digital Processes)

Weaving. Photographer unknown. Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8” (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Binary information was probably first used in mechanized textile looms, as early as the eighteenth century. This contemporary example achieves about thirty-two levels of tone using only black and white threads (not counting the transparent threads in the weft). The process simultaneously produces positive and negative images on opposite sides of the fabric.

This piece of cloth, which can be viewed from both front and back, is a picture of Chairman Mao. Probably woven in the 1980s, it is nevertheless full of lessons about the history and technique of printing and photography. First of all, it is a piece of weaving that holds a representational picture.

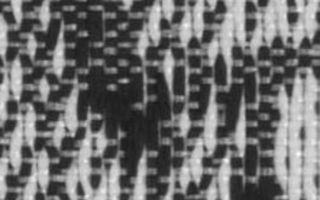

Detail of Weaving. Photographer unknown. Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8” (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Pictures of all kinds—representational, decorative, symbolic—have long appeared in weaving, but this one was made with a Jacquard-type loom, a loom driven by punch cards that translated the tones of the image into patterns of stitches displaying values from dark to light. Invented at the start of the nineteenth century, these looms are the first known practical instance of binary numerical data being applied to a visual end. The one that wove this was already obsolete when it did its weaving. Chairman Mao might be made of threads woven into cloth, but he unquestionably started out as a photograph. This is the second lesson from this weaving. We should understand that the description of the world made by lens and camera is radically unlike that of traditional artists.

Weaving. Photographer unknown. Back of Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8” (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line, c. 1980. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

When a portrait painter made a picture of a famous figure, the form and content of the picture inevitably revealed what was thought about the subject—what the artist, the sitter, or both wished to have projected to the viewing audience. Photography, on the other hand, makes its pictures out of reality, and brings to the viewer objects and structures whose description is far from the traditional ideals. Mao’s pudgy hands, the tabletop on which they rest, and the inactive pencil were the photographer’s props, but their appearance comes from the world itself, without the embellishments of traditional art. We must not confuse a photograph with the world from which it is made, but there is little question that photography’s connection to that world gives it a radically new visual character when compared to the old handmade pictures.

Detail of Weaving. Photographer unknown. Back of Chairman Mao. c. 1950. 11 1/4 x 14 1/8” (28.5 x 35.8 cm). Printed by Silk Line. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The third lesson comes from the back of the cloth. The weaving was done with two sets of threads in the weft: one black, the other white. Tones were made by grouping stitches in a grid and controlling the amount of white and black shown in any given grid area. The interesting thing is that as white threads were shown on the front, the black threads had to move to the back, and vice versa. So the positive image on the front generated a negative one on the back. This is a beautiful way to see the relationship between positive and negative: if you have an even tonal field and remove a positive picture from it, a reversed negative image remains. Almost all color photography would end up using this principle to generate positive images in one step.

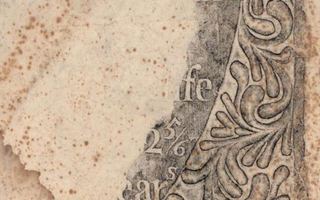

Rubbing. John Stevens. Decorative tombstone border carved in slate. c. 1715. 17 1/2 x 11 1/4” (44.5 x 28.6 cm). Printed by John Howard Benson. c. 1940. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The most basic pictorial analog is the rubbing. Since I come from a stone-carving family I can’t resist illustrating one made from an early American tombstone. The letters and floral border are beautifully described, and the picture has that marvelous characteristic of only showing part of the original, like some Greek sculptural fragment where the arms and head tantalize us with their absence. This sheet also has a great patina of brown spots running across the surface and there is even a large water stain on the bottom edge. All in all it makes a great picture, and does so by transmitting information from the original carved stone into a new context: the meaningless degradation of the paper support. The artists among us should always be cautious about letting such beautiful haphazard patterns coexist with intended meaning.

Rubbings are extremely easy to make. This one was done by holding a soft sheet of paper against the vertical stone and then rubbing the paper surface with a block of black cobbler’s wax called “heel ball.” Multiple rubbings aren’t too good for the object underneath, but if the work is done with soft ink-bearing pads, virtually no harm is done to the original. A few artists use rubbing as their medium, laying down different colors with different pressures to make rich renditions that owe as much of their content to manual skill as to the mechanical transmission of information from one form to another.

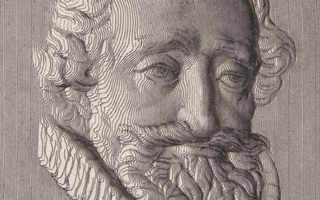

Pantographically derived etching. Artist unknown. The Head of Henry IV. n.d. Relief medallion. 1837. 3 3/4 x 3 3/4” (9.5 x 9.5 cm). Printed by Achille Colas. From “Answer to Mr. Bate’s Challenge,” Literary Gazette no. 1047 (London), February 11, 1837. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The nineteenth century was the age of commemorative relief medals. They were made to honor notable occasions and famous people, and were cast in multiple copies of great precision and beauty. I came across a book of extraordinary etchings made from these medals, and include one here because the etched printing plates were generated mechanically from the medal’s relief modulations. The work was done with a pantograph, a mechanical device that uses a series of bars on pivots to trace forms and produce analogs of them in different sizes. Pantographs were used in silhouette-making, and to reduce or enlarge drawings and sculptural work. In this particular case the pantograph was asked to translate the vertical modulations of the medal’s surface into variously spaced lines scored in an etching ground. One end of the pantograph ran over the medal and was constrained to run in a straight line only.

Detail of Pantographically derived etching.Artist unknown. The Head of Henry IV. n.d. Relief medallion. 1837. 3 3/4 x 3 3/4” (9.5 x 9.5 cm). Printed by Achille Colas. From “Answer to Mr. Bate’s Challenge,” Literary Gazette no. 1047 (London), February 11, 1837. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

In the background of the print, showing the flat part of the medal, vertical, close, evenly spaced parallel lines produced the effect of an even tone. When the operator raised the tracing stylus by moving it over the relief section of the medal, the line being drawn in the etching ground by the other end of the pantograph was shifted slightly to the right (actually to the left, because the print is reversed). By running the stylus repeatedly across the medal’s surface, and shifting each line minutely forward from the one before, the printer drew a topographical map of the medal on the prepared plate surface. Once etched, this plate could be inked, wiped, and printed to produce the picture we see here. It is a remarkable process, and only understandable by looking at highly magnified sections. The changing spacing between the lines causes a lightening in areas that rise up on the left of the print; as the form begins to fall off on the right side, the line spacing is reduced and the tone darkens. The increasing and diminishing of the line spaces is perfect, so that the flat surround retains its even gray tone even while the lightening of the head on one side is perfectly compensated for by a darkening on the other. The viewer’s impression is that the medal has been lit from the left side—an apparently perfect lighting, coming not from one point but from parallel rays skating at a low angle across the surface of the medal.

Silhouette. Anna Wharton. Phebe A. Hough. 1856. 12 1/2 x 12 5/16” (31.8 x 31.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson

For much of the previous century, the cutting of silhouettes had been a pastime at parties and family gatherings. They were made through the use of light, by tracing the shadow of a person’s profile. The traditional way to do it was to have the subject sit with a book, or some like-shaped object, pressed between their head and the wall, and with a piece of paper between their head and the book. The book both supported the piece of paper and served the useful role of keeping the subject from moving. A candle across the room cast a shadow; this outline was traced, the paper was removed, and the silhouette was cut out from it with scissors. Multiple copies were often made so that everyone could take the pictures home with them as mementos. In viewing a silhouette, we are most often looking at negative space—not the positive figure but the white paper from which it has been cut, and which is set against a sheet of black paper.

Although this picture-making practice goes back into the eighteenth century, well before the invention of photography, the pictures it produced have always seemed to me as photographic as anything else: they record the actual form of the subject, and it is very easy to identify silhouettes of those one knows. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, silhouettes of full-length figures were made, not based on the tracing of light but cut by eye. Similar silhouette-making is done today at carnivals and tourist destinations, with the maker usually just looking at the person to be depicted and then cutting a reduced-size silhouette directly. This method is closer to caricature than to photography, since the outline comes from an image in the maker’s mind, rather than being generated by some mechanical means from the subject itself.