Silver-Based and Non-Silver-Based Photography, Pt. 1

In this segment, taken from his 2008 talk at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for his exhibition The Printed Picture, Richard Benson walks us through the early processes of printing photography in silver. He gives an overview of salted-paper prints, wet-plate photography, albumen prints, ambrotypes, tintypes, and gelatin-based printing-out paper. Pictures associated with each of the main themes presented in the segment can be found by clicking on any of the section links below.

Early Photography in Silver Introduction (see Bits and Pieces)

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a woman. c. 1858. 3 5/8 x 2 3/4” (9.2 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

I always like to say that photography had five inventors. We all know three: Niépce, Daguerre, and Talbot. A fourth, my favorite because of his pictures, is the Frenchman Hippolyte Bayard, who invented an autopositive paper process in the early 1840s. The fifth would be Sir John Herschel, a member of that small group of the wealthy English upper class who all seemed to know each other in the mid-nineteenth century. Herschel solved the great problem of how to make photographs permanent, suggesting to Talbot that he “fix” his pictures with the chemical sodium thiosulfate. This compound, and its cousin ammonium thiosulfate, have remained the primary fixing chemicals for nearly all silver-based photographic processes, from the very earliest until those modern chemical processes that are presently disappearing under the digital onslaught.

The invention of photography was formally announced in 1839. During the previous decades, though, many people had worked on the task of capturing an image by the agency of light alone, and as early as 1826, a Frenchman, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, had made a lens-generated image in hardened asphaltum. What happened in 1839 was that two completely different processes reached a practical state of development that would quickly allow photography to spread throughout society. One method—invented by another Frenchman, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre—allowed precise and sharp lens images to be captured on silver-plated sheets of copper. The other method, invented by the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, produced rougher images on paper.

The Daguerreotype (see Bits and Pieces)

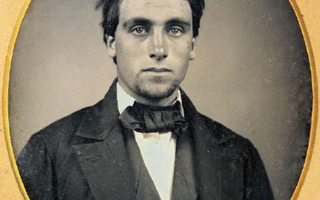

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a young man. c. 1860. 3 1/4 x 2 3/4” (8.3 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

All photographic capture methods from 1840 until the development of digital technology depended upon the sensitivity of silver compounds to light. By photographic “capture” I mean the generation of specifically lens-based images. Through the balance of the nineteenth century, many processes evolved for photographic printing, a number of them using not silver but other compounds responsive to the high levels of illumination that could be used to print photographic negatives by contact. But only silver salts were sensitive enough to record the relatively weak light that could pass through an image-forming lens. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s invention—a method of hardening asphaltum by exposure to light—came first, but it turned out to be a complete dead end for photography per se; it was too insensitive for use in a camera.

Daguerreotype. Photographer unknown. Sarah Anna Chace Greene and Her Children. c. 1850. 3 5/8 x 4 1/4” (9.2 x 10.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Silver dominated photography for a century and a half, and from the start it exhibited two completely different ways of making images. The first method in which a silver compound darkens directly as it is exposed is referred to as “printing out” and was essential to the earliest paper processes. The second, which uses the ability of some silver compounds to hold a latent image, invisible yet developable was the basis of the daguerreotype and of all of the glass and film processes that followed. It is of the utmost importance to recognize this miracle of some silver compounds that they not only respond to light in a manner that can be made permanent, but do so in two radically different ways.

Daguerreotypes were made by silver-plating a sheet of copper, then treating it with an iodine compound to produce a coating of light-sensitive silver iodide. After exposure the plate was subjected to mercury vapor, which condensed onto the latent image, most thickly where the light had been brightest. When the silver areas in a daguerreotype reflect a dark ground, the mercury appears as diffuse white, producing a positive image. After the formation of the mercury image, the plate was “fixed” with sodium thiosulfate, which photographers nicknamed “hypo.” As a final step the pictures were toned with gold, which stabilized them and made the image more robust. Since the metal support did not absorb these destructive fixatives, the daguerreotype avoided the fading that has always plagued paper photography, but all daguerreotypes had to be sealed to prevent tarnishing of the silver coating upon which the mercury image rests. The small frames, glass covers, and cases in which daguerreotypes live add a whole layer of physical protection.

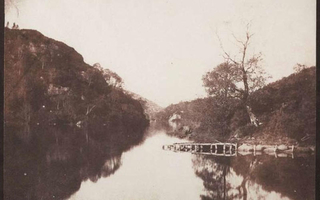

Salted-paper print from a calotype. William Henry Fox Talbot. Loch Katrine. 1844. 6 7/8 x 8 5/16” (17.4 x 21.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund.

The silver compound most commonly used in early photography was silver chloride, which involves an interesting technical problem in that it is completely insoluble in water. You cannot make a solution of silver chloride and coat it on a sheet of paper, no matter how hard you try. The way around this problem was to coat the paper with a salt solution—perhaps even using plain old table salt—that had a small amount of gelatin mixed in as a binder. Once that coating was dry, a second coating, of a solution containing silver nitrate, was put on the sheet.

The moment the silver nitrate and the salt came into contact they produced silver chloride, and because the salt was evenly coated, the silver chloride was as well. This is the origin of the term “salted-paper.” It was possible to apply the salt coating and then dry and store the sheets; the silver nitrate had to be applied shortly before the material was used, since the sensitive paper degraded in a day or so. Virtually all salted-paper prints were toned with gold prior to fixing, which gave them their characteristic reddish-purple color.

Wet-plate. Lewis Carroll. The Terry Sisters. 1875. 6 x 5” (15.2 x 12.7 cm). Printed by Richard Benson, 1980. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Early photographs on paper were poor in their rendition of tone and detail because the negative image was imbedded in the rough paper of the support. The negatives were usually waxed, to make them translucent and to reduce the effect of the paper’s fibers, but even so the images they produced could not compete with the daguerreotype for precision and exactness. A tremendous improvement came in the 1850s with the invention and refinement of the wet-plate process, which used a glass support for the negative and captured sharp, intricately detailed images that could be printed with a long and smooth range of tones. We can say with some confidence that with the wet-plate process the image quality of black and white photography reached a level that matches anything done since.

Detail of Wet-plate. Lewis Carroll. The Terry Sisters. 1875. 6 x 5” (15.2 x 12.7 cm). Printed by Richard Benson, 1980. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Like the daguerreotype, a print from a glass-plate negative has superb tonal description, as we can see in this six-times enlargement from the print.

The process only worked when the coated glass plate was exposed while still damp, which meant that the photographer working outside the studio needed a portable darkroom. Hardworking photographers lugged their plates and cameras all over the world, and since no good enlargement process existed—printing was only done by direct contact between negative and paper—those plates and cameras were generally as large as possible.

Albumen print. George Washington Wilson. Marischal College, Aberdeen. c. 1875. 4 1/2 x 7 1/2” (11.4 x 19 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The wet-plate era demanded a new printing process that could do justice to the wide range of tone held in the glass negatives. The older method of printing on paper—the salted-paper method—produced images that sat directly on the paper fibers, which made them somewhat rough. They were also completely matte, which meant that they could never have strong black values; matte surfaces diffuse the light reflecting off them, preventing the high degree of light absorption that is necessary to portray a strong black value. Because of their superb scale the wet-plate negatives opened the door to a new range of tonal description in the darker values that had not been possible with the salted-paper process.

Albumen print. George Washington Wilson. Market Cross, Aberdeen. c. 1875. 4 1/2 x 7 1/2” (11.4 x 19 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The solution was albumen printing. The name comes from the fact that the image-bearing material was held onto the paper support by a relatively thick layer of albumen, the soluble protein found in egg white. This binder allowed prints to be made that carried the image not on the paper fibers but above them, in the smooth egg-white coating. Albumen also produced a beautiful semigloss surface, which could describe a very dark value if enough silver was present—and in fact the new method increased the amount of silver available in the print. The albumen coating could hold far more sensitive salt than salted-paper did and hence could produce a much heavier metallic deposit.

The combination of the wet-plate negative and the albumen print transformed positive/negative photography; once this pair of techniques spread, the daguerreotype was effectively dead. It is important to review just what changes these new processes represented. In the older salted-paper-based photography the negative was exposed dry, had a low sensitivity, and produced a rough and tonally limited image. The newer glass negative was far more sensitive, held superb detail and tone, but had to be coated and exposed just moments before being used. In printing, both the old and the new method used a sheet of paper that was exposed dry, by contact, fixed with sodium thiosulfate, and then toned with gold. A thorough wash in plain water removed any residual chemicals. In both cases the image “printed out,” so no developing was needed. The chief difference between the salted-paper and the albumen print was simply the binder used to hold the sensitive salts (and subsequently the image) onto the paper support. The use of albumen gave the prints a new surface, deeper tonality, and far more detail. In many ways albumen printing was just an improved version of the older salted-paper. The wet-plate negative, on the other hand, had been a radical innovation.

Ambrotype. Photographer unknown. Portrait of a man. c. 1880. 3 5/16 x 2 3/4” (8.4 x 7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Most photographers who have worked in the darkroom are aware that negatives can sometimes appear as positives. Often we will lift an underexposed negative out of the fixer, disappointed that it is of insufficient density, and find that it suddenly appears as a positive. This occurs when the silver deposit is illuminated by the overhead light but we see it against a dark background, perhaps the old darkroom trays made of black rubber. The silver, which appears light gray, shows as a positive instead of a negative, since it is much lighter than the background against which we see it. This phenomenon was noticed early on, and some wet-plate photographers turned it to use by intentionally underexposing their plates, then coating the back of the glass with black paint. The resulting pictures—unique, direct-positive images— were called ambrotypes. Usually small, they were put in cases and entered the same market as the dying daguerreotype.

Tintype. Photographer unknown. Arthur Cleveland. c. 1895. 4 x 3 1/4” (10.2 x 8.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Arthur Cleveland grew up and lived most of his life in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. As a middle-aged man his portrait was painted by Andrew Wyeth.

The tintype was a variant of this process, made by applying the wet plate coating not to glass but to a sheet of black-lacquered metal. The tintype survived for years. It was cheap, easy to do in a small size, and because the metal base didn’t absorb water it could be exposed, developed, dried, and then immediately given to a tourist or other traveling customer to carry away. Part of the problem with both the ambrotype and the tintype was that they were unique—each exposure produced just one picture. Like the daguerreotype, every one still around once sat in the camera facing its subject; it is a relic of the origins of photography. Another drawback was that the highlights were always gray—the beautiful white of paper, capable of holding a long range of tones, did not exist for either process.

Gelatin-based printing-out paper. J. Thompson. Stoney Creek Bridge, Selkirks, C.P.R. c. 1893. 9 1/8 x 7 7/16” (23.2 x 18.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Albumen, the giant of all the nineteenth-century photographic printing mediums, was doomed by the spread of the dry plate, but it underwent a few changes on its way out. Gelatin printing-out paper (POP) was the most widespread of these. Gelatin is a tremendously versatile material, and it was mass produced. (It was a byproduct of animal husbandry—sending the old horse to the glue factory meant it was to become a source not just of glue but of gelatin and animal feed.) Once purified, this organic polymer behaved predictably and lent itself to manufacturing processes with a dependability and ease that albumen did not. A gelatin POP differed from an albumen sheet only in the substitution of gelatin for egg white as the binder that held the silver salts.

Detail of Gelatin-based printing-out paper. J. Thompson. Stoney Creek Bridge, Selkirks, C.P.R. c. 1893. 9 1/8 x 7 7/16” (23.2 x 18.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. An eight-times enlargement from the original print.

This new paper was still exposed to the sun, it printed out with no developing necessary, and it was gold toned for permanence before fixing. The surface of these new prints, though, was hard and glossy. Albumen’s beautiful, articulated, semigloss surface gave way to the high shine that later modern papers would also have, since they too would be factory coated with gelatin emulsions. While albumen paper had completely disappeared by the 1920s, gelatin printing-out paper continued to be made throughout the twentieth century. Because it produced a superb image that needed no developing, portrait photographers could easily make prints on this paper as proofs for their customers. Being neither gold toned nor fixed, the pictures would gradually darken as they were viewed, so the client would have to come back to the photographer to buy a permanent, final print.