This detail from a copy of Van Dyck’s painting shows the image that Beckett copied when he made the mezzotint. All direct printing processes, in which the plate transfers ink to the paper in one step, reverse the image. The image on the plate of the mezzotint had the same orientation as the painting; once printed, it was flopped horizontally.

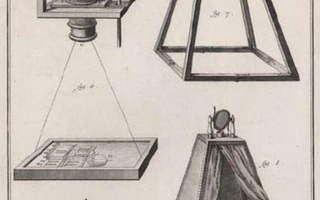

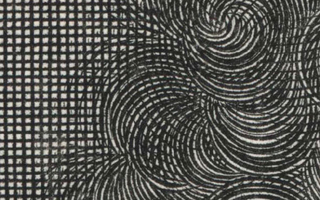

When this tool was rocked firmly back and forth on the plate, and gradually moved across it, the plate took on a mixture of indentations and raised burrs across its entire surface. If inked, a plate thus prepared would have printed a smooth black tone. First, though, the artist worked on it with a burnisher, a small handheld tool with a rounded, highly smooth tip. The polished areas of the surface held less ink than the rougher ones and produced the lighter tones of the picture. The process is considered intaglio—printing from the low—but as well as sinking grooves, the rocker raised burrs that probably held just as much ink, making the technique in many ways related to drypoint.

However we classify it, mezzotint produced beautiful values and a fundamentally different look from any other kind of print, but the plate was extremely delicate and had to be printed with great care. Mezzotint editions were far smaller than those of engravings or etchings because of this fragility of the plate. It is very hard to make a good picture with an eraser, which is what the artist was doing in burnishing the plate. In many mezzotints, then, the technique dominates the image and the pictures suffer accordingly. The beautiful and eccentric picture of King Charles of England shows the tonality that mezzotint made possible, but also its potential weaknesses: uneven areas of large tone when no detail is present, and a somewhat odd appearance in the lighter values, which comes from the difficulty of knowing just how the burnished plate will carry ink. When mezzotints were just right, though, their beauty was breathtaking and their degree of technical refinement astonishing.