Silver-Based and Non-Silver-Based Photography, Pt. 3

In this segment, taken from his 2008 talk at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for his exhibition The Printed Picture, Richard Benson walks us through processes associated with modern photography. He gives an overview of the dry plate, developing-out gelatin silver paper, and the Kodak Number 1 camera. Pictures associated with each of the main themes presented in the segment can be found by clicking on any of the section links below.

Modern Photography Introduction (see Color Notes)

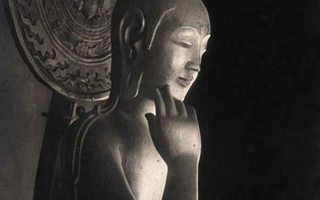

Gelatin silver print. Attributed to Shotoku. Nyoirin Kwannon. c. 556 (printed c. 1933). Sculpture in black lacquered wood. Photographer unknown. 10 3/4 x 8 3/4” (27.2 x 22.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The era of modern photography began with the great innovation of the dry plate. Now that camera-ready materials could be purchased off the shelf, the medium underwent far more than a technical change: the physical manipulations of photography shifted to the background and concerns with picture content came to the front. According to the photographer Tod Papageorge, this invention opened the door for photography to become more like poetry than carpentry.

Gelatin silver print. Frank Jacobs. Portrait of Mother and Son on Mount Rainier. c. 1930. 13 15/16 x 10 15/16” (35.4 x 27.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Gelatin silver print. Photographer unknown. Reece Franklin (on the right) and friends in Washington State. c. 1938. 5 1/4 x 3 1/2” (13.3 x 8.9 cm).

Gelatin silver print. Nicholas Nixon. View of the New John Hancock Building. 1975. 7 5/8 x 9 5/8” (19.4 x 24.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Nicholas Nixon.

This print was made by contact on Kodak Azo paper, a silver chloride based, contact-speed, gelatin developing-out paper that remained available long after other such papers disappeared from the market.

Gelatin silver print. Clarence Kennedy. Madonna and Child (Tondo Relief of the Madonna and Child). 1933. 11 x 8 3/4” (28.0 x 22.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mrs. Lester Talkington in memory of her father, Clarence Kennedy © Estate of Clarence Kennedy.

The transforming technical innovation that created modern photography was the dry plate. Invented in the late nineteenth century, this new negative material completely supplanted the wet-plate process. All the old photographic technologies, whether for capturing images in cameras or printing them on paper, were chemical systems that the photographer assembled from raw materials. Photography had been much like cooking, with recipes to guide the practitioner, and secret formulas jealously guarded. The dry plate was a completely different thing. As the name implies, it was a light-sensitive plate that could be used dry without the need for immediate assembly that the wet-plate required. There is a large difference in the light energy needed to make a negative and to make a print.

The negative is usually made in a camera, whose lens focuses the light that goes through it so that any point on the negative only receives light from a single point on the subject. Because they were used dry, these plates could be manufactured and sold later on; because they were hard to make, their manufacture was taken out of the hands of photographers and instead was done in large manufacturing plants. These two changes marked the turning point between old and new photography. The dry plate held a light-sensitive silver salt in a gelatin emulsion on glass. The plates were far more sensitive to light than the older wet-plate; we say they had more “speed.” The coatings were also perfect, something that had never happened before, and to top it all off, any given box of plates tended to be absolutely consistent in quality. All of these characteristics gave photography a great boost in ease of use, as they took the task of making materials out of the hands of the artist. A similar thing had happened in painting when paints and canvas became available in manufactured form, but painting is difficult whether we make our own paints or not. Photography, on the other hand, turned out to be remarkably easy if the materials came in a store-bought box and had only to be exposed and developed. Whether the pictures so made were good or not is another question altogether. It is impossible to know if the dry-plate era made photography better or worse. The technology of dry-plate coatings quickly moved over to flexible film and then to paper for printing purposes. These new chemical coatings, whether on glass, film, or paper, completely supplanted all the older photographic processes. Wet-plate, albumen, platinum, and carbon all went into the junk heap under the assault of inexpensive, easy-to-use materials bought off the shelf of the local supplier. Now that the technical success of the picture was taken for granted, photography as a medium had to scramble to get its content back.

Gelatin silver print. Benozzo Gozzoli. The Tower of Babel fresco, Campo Santo, Pisa. c. 1470. 7 x 9 1/4” (17.8 x 23.5 cm). Printed by unknown photographer. c. 1910. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The story of the dry plate hovers in the background of photographic history because at first it was used to make negatives, artifacts that are never seen by the viewing public or bought by the traveling tourist. Negatives slide back into envelopes, to be printed later for new orders or to be simply lost in the closets of amateurs. When the dry-plate chemistry moved over to the printing side of photography things really began to look different.

Gelatin silver print. Benozzo Gozzoli. The Tower of Babel fresco, Campo Santo, Pisa. c. 1470. 7 x 9 1/4” (17.8 x 23.5 cm). Printed by unknown photographer. c. 1910. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The gelatin coating of the dry plate, put onto a paper support, produced our modern “gelatin silver paper” (as the museums call it). This material uses the latent image—no more printing out—and produces an image color that is far closer to neutral than most earlier photographic printing processes do. The papers were exposed and then had to be developed, so we can call them “developing-out papers,” or “DOP” (as opposed to the older POP, or printing-out papers).

It really wasn’t until the spread of gelatin silver papers and dry-plate negatives that the darkroom came into its own. Most nineteenth-century printing materials could be handled in room light and even the wet-plate could be manipulated under a red safelight. The new papers were in some cases as sensitive as the film was, and light-tight darkrooms became standard in photographic practice. Early in the twentieth century, dry-plate materials began to be made with full color sensitivity, and these required absolute darkness for handling films and plates. The neutral tone of the new papers caused a stir. Except for relatively rare processes such as carbon, platinum, and blueprint, photographic printing had mostly been reddish purple, and in some way the new prints didn’t seem to be “real” photographs in the way the older albumens had. The woodburytype printers had had a similar problem, and had often used purplish pigments to make the viewer think the prints were albumen. It didn’t take too long for the public assessment to shift, and for photographers and their clients to accept neutrality as the norm in photography, but we find prints from the transition period that were made the new way but toned to look like the old. The pair shown on the previous two pages is a perfect example. Both pictures were made for the tourist trade, and, because I found them together and they are of the same subject, it was assumed they were made at about the same time. Both are on modern developing-out gelatin silver paper, but the lower one has been toned—quite beautifully—to imitate an albumen print. Toning hung around for a while, but later on it tended to be done to make the prints somehow more “artistic.”

Gelatin silver print. Photographer unknown. Kodak #1 print. c. 1890. Page: 7 x 10 3/16” (17.8 x 25.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

If we think of the development of photography as some sort of evolutionary process taking the form of a branching tree, then we could say that the tree split, and grew a second trunk, with the development of George Eastman’s amateur cameras. Eastman cobbled up a system combining his own ideas with those of others and produced cameras that were sold preloaded with a roll of flexible film. The user exposed the roll, then shipped the whole camera, its film inside it, to the factory for processing. The film was processed, the camera was reloaded with a new roll, and camera and prints were mailed back to their owner. All the user had to do was aim the camera, click the shutter, and use the mail—all of the technical chores were taken over by Eastman’s company. These extremely basic cameras used a single-element lens and a single-speed shutter.

Gelatin silver print. Photographer unknown. Kodak #1 print. c. 1890. Page: 7 x 10 3/16” (17.8 x 25.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Because the lens was crude it did not cover the corners adequately so a round mask was placed in front of the film to crop them out, making the earliest Kodak pictures round in format. It was also a very wide-angle lens, which meant that as often as not the subject managed to be in the picture, despite the inaccuracy of the camera’s viewing system. The wide angle of view from such a short-focal-length lens produced a description of the world very different from the previous photographic norm. For centuries, painters had been structuring their pictures so that figures, buildings, and landscapes appeared “normal,” which is to say undistorted by a close point of view. We can even go so far as to say that the vision of the traditional painter was that of a photographer using a long lens. The Kodak camera, with its short-focal- length lens, distorted the perspective of a scene when compared to traditional pictures.

We can see this distortion in the two photographs shown: feet in the foreground turn down and enlarge as they approach the picture edge. Trees in the picture on the previous page go from very tall to very short as they run from left to right. The young woman in that photograph, who appears abnormally small compared to the two men in front of her, is not in fact so small; her odd size is a result of the picture structure. While her head is lower than the men’s, her feet also have risen up in the picture plane. Both these shifts of scale derive from the lens. In some ways we can say that the history of photography has been one of steadily shortening focal lengths. From the classical, distanced view of the painter, photographic description shifted to encompass wider and wider angles of view. Both Eugène Atget, the great French photographer who so often worked in cramped spaces, and George Eastman, the American entrepreneur, moved photography a huge step in this direction through their adoption of radically descriptive wide-angle lenses.

Contact Printing (see Color Notes)

Gelatin silver print. Nicholas Nixon. View of the New John Hancock Building. 1975. 7 5/8 x 9 5/8” (19.4 x 24.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Nicholas Nixon.

A properly made contact print is virtually as sharp and tonally rich as the negative from which it is derived.

By the 1920s modern photographic papers had evolved into two classes. One group had a low sensitivity to light, and were referred to as “contact” papers. The other group were highly sensitive—some even approaching film in their speed—and were made for use in the enlarger, to make big prints from little negatives. Both of these modern papers were far more sensitive than the older POPs, which had required light of the sun’s intensity for exposure. The first type of these new papers was used by placing negative and paper into a spring-loaded frame, so that the emulsions of each were held closely together. Then an exposure was made with a normal lightbulb from a few feet away.

Gelatin silver print. Josef Koudelka. Wales. 1977. 8 x 11 3/4” (20.3 x 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Joseph Koudelka.

The second type of paper was exposed in an enlarger, which is really just a camera turned inside out: the small negative is held in a frame and brightly illuminated from behind, and the light passes through it to a lens, which projects the picture onto the paper at a larger scale. I call the enlarger a camera because the subject being photographed is the negative and the print paper takes the role of the film.

Unlike a normal camera, the enlarger contains both light and subject within a light-tight bellows, while the paper recording the image is out in a large dark room. This inversion of light and dark allows the printer to manipulate the light on its way to the paper, altering the overall tonalities by shading with hands or specialized tools. The two classes of paper were based on two different silver salts. The slower paper was usually made with silver chloride, which produced a warm tone. The faster, enlarging papers were usually made with silver bromide, which produced colder colors. Many intermediate papers were produced with mixtures of these salts, and the manufacturers kept the formulas for them secret. By the 1930s a wide variety of papers was available, in many surfaces, speeds, and subtle colors (although all of them were basically neutral). The emulsions of many of these papers contained a great deal of silver. The papers were coated slowly, and had a relatively soft gelatin surface that was delicate but very beautiful; these papers could produce tonally rich prints. As the technology of manufacture advanced over the years, the silver content went down and the coating speeds went up, giving less appealing surfaces. At one point the manufacturers added a top coating to the papers, called a supercoating, made of harder gelatin, which made them easier to handle. As time went by, emulsion design was greatly improved, and even with less silver and harder surfaces, today’s materials are as good as if not better than anything made in the past.