Printing from the High Parts

In this segment, taken from his 2008 talk at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for his exhibition The Printed Picture, Richard Benson walks us through the process of relief printing. He gives an overview of relief prints on cave walls, woodcut printing, the art of the hand-lettered manuscript, the letterpress, the use of woodcut and metal type, wood engraving, stone lithography, and stencil lettering. Pictures associated with each of the main themes presented in the segment can be found by clicking on any of the section links below.

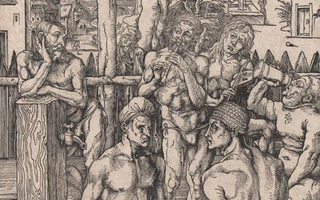

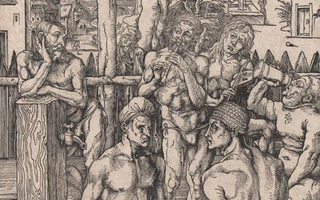

Woodcut. Albrecht Dürer. The Men’s Bath. c. 1496. 15 7/16 x 11 3/16” (39.2 x 28.4 cm). Collection of John Benson.

Printers have had to devise methods of creating tonal variation using only black ink. One solution is to use finely spaced lines that, though black, give the eye the illusion of tone when viewed from a distance.

The oldest and simplest of all printing processes involves printing from the high parts of some surface. In the picture we see here, printed by woodblock, parts of the block’s surface have been cut away, and leave no mark, appearing in the image as white. The high parts of the block have not been cut away, and they print black. We call this class of printing “relief” printing.

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8” (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

The invention of metal type transformed Western culture by fostering the wide dissemination of texts.

Letterpress from wood engraving. Thomas Nast. That Everlasting Hungry Wail from Harper’s Weekly. October 10, 1885. 14 3/16 x 9 9/16” (36 x 24.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A two-color wood engraving by an anonymous engraver from a drawing by Nast.

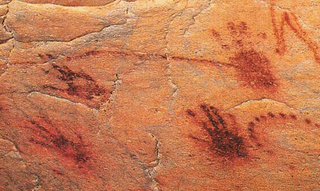

Pigment prints. Artist unknown. Hands from the walls of the Chauvet cave, Ardèche, France. c. 30,000 B.C. © Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps, and Christian Hillaire.

Mixed in with the hand-drawn pictures in the caves are clear examples of printing. The most common of these printed pictures are of the human hand. Sometimes the image is dark, obviously made by impressing a pigment-covered hand onto the wall, while in other cases the hand appears as a negative, clear but surrounded by colored material. The hands we find in prehistoric caves represent two of the fundamental forms of the basic types of printing. The positive images (those made by the hand itself carrying the pigment) are examples of relief printing, the system that underlies printing with moveable type or with wood or linoleum blocks. The negative images (those blank hands surrounded by colored pigment) are examples of stencil printing, in which image-bearing pigment is passed through or around some form that holds the picture information.

Pigment prints. Artist unknown. Horses from the walls of the Chauvet cave, Ardèche, France. c. 30,000 B.C. © Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps, and Christian Hillaire.

Woodcut. Albrecht Dürer. The Men’s Bath. c. 1496. 15 7/16 x 11 3/16” (39.2 x 28.4 cm). Collection of John Benson.

The intention is to explore this many-layered subject through an examination of the different ways in which printed pictures are made. An underlying premise is the fact that printing, photography, and digital technology, as applied to pictures, are all aspects of a single ancient process: that of creating fixed visual forms in multiple copies. I believe that pictures are as important as language, and that together they form the glue that holds society together.

As far as possible the texts follow a chronological thread, but because the various processes have originated and disappeared at different times, and because the texts and pictures are grouped by process, there is necessarily some jumping back and forth in time.

Enlargement of Woodcut. Albrecht Dürer. The Men’s Bath. c. 1496. 15 7/16 x 11 3/16” (39.2 x 28.4 cm). Collection of John Benson. A detail enlarged about 1.2 times from the original print.

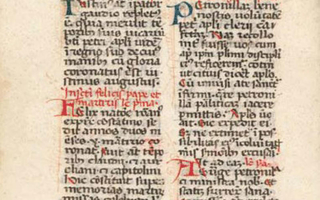

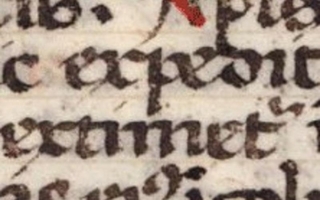

Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8” (14.6 x 10.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand.

This small and simple manuscript page dates from the fourteenth century. The letters are run-of-the-mill, written rapidly by a scribe on a sheet of calfskin. This is not part of a large and splendid Bible, worth thousands of dollars; rather it is a remnant of a Catholic missal that I bought in a junk shop for $20 some years ago. Before the invention of lead type such pages existed by the hundreds of thousands. Bound up in books, they were the primary carriers of language in a fixed form, as opposed to the fluid and changeable information buried in the spoken word. Centuries before this page was written, human culture had learned the remarkable lesson that language could be laid out, in all its tremendous variety, through the use of a limited set of letters and words.

Detail from Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8” (14.6 x 10.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand.

Handwritten letters can vary according to their neighbors, and individual letters often run together. This practice gives a strong identity to the words, and reinforces the fact that letters by themselves mean nothing; content only exists when words and sentences are formed.

This persistence has shown that accumulated knowledge, set down in ink on paper, has the ability to last through generations. In the animal kingdom some artifacts do last—pathways and burrows can be used over decades—but by and large the knowledge each individual accumulates through experience dies once the biological shell fails. The written word gave humanity a tool far beyond that of any other animal; it is the perfect Darwinian step to ensure the survival and dominance of the species.

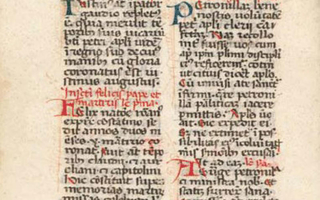

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8” (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Handwritten manuscripts were costly to make, and could exist only in limited numbers, available to the well-to-do and the powerful. In the mid-fifteenth century, in their efforts to produce less expensive versions of written language, printers began to use metal type, unleashing the great revolution of language-based information available to the masses. Prince and pauper alike got the same information from the printed page, and I have always thought that democracy as we know it would have been impossible without this innovation. The use of metal type spread rapidly, and over the 400 years from 1500 to 1900 the technology of printing words by making them up out of little metal letters in relief remained basically unchanged.

Hand lettering. Artist unknown. Page from a missal. c. 1350. 5 3/4 x 4 1/8” (14.6 x 10.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A small manuscript page written in a southern Gothic book hand.

Technological innovation tends to derive from need, and the development of printing from moveable type was such an innovation that its initial technology did not require much further development for this astonishingly long period.

Letterpress from woodcut and metal type. Anton Koberger and the workshop of Michael Wohlgemut. King Friderich and the Roman Pope, page from the Nuremberg Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel. 1493. 13 3/8 x 9 15/16” (34 x 25.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

Because the side-grain block used for woodcuts was not stable enough to lock up well on the press with metal type, words and pictures were not usually printed together before the advent of wood engraving in the nineteenth century.

Since the very beginning of printing on paper, printers have struggled to accommodate words and pictures on a single page. Both types of images are pictures—the former symbolic and the latter representational—but the methods used to print them have been very different.

Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8” (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.

This page, an early effort to combine words and pictures, was made by locking a woodcut into the chase along with the letters and furniture. This was a dubious practice: the woodblock could be made type high, so that the printing surfaces of both picture and words came to the same level in the press, but the block was flexible while the type was not. As the wedges used in the “form” (the printer’s name for the assembled contents of the chase) pressed the assembly together, the woodblock, at right angles to the direction in which it had grown in the tree, would compress.

Detail of Letterpress from metal type. Mark and Charles Kerr, Edinburgh, printers. Holy Bible, page from Jeremiah 51. 1795. 9 11/16 x 8” (24.6 x 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. k. Gift of Richard Benson.

The metal type, on the other hand, would hold its shape under pressure, so picture and letters were held with different degrees of firmness and the whole package was unstable. Such instability could be tolerated in a slow, manually driven hand press as long as the printer kept a close eye on the chase and its contents, but the system could never work once the presses ran at any sort of speed. The page from the Nuremberg Chronicle was made in 1493, well before the arrival of the steam-driven printing press, so it could be slowly printed by this union of side-grain wood and metal type. Three hundred and fifty years later, when presses were mechanically driven at high speeds, a different method for uniting words and pictures would be needed.

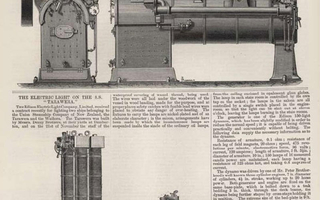

Letterpress from wood engraving and metal type. J. H. Rimbault. Compound Semi-fixed Engine from the journal Engineering, December 8, 1882. 1882. 12 x 8¾” (30.5 x 22.2 cm).

The solution to the problem of combining words and pictures on press came in England in the late eighteenth century, with Thomas Bewick’s refinement of wood engraving. Bewick worked as an artist, making precise, beautiful, tiny wood engravings, but the process quickly became established as a commercial system for printing illustrations because the wood engravings could be used in conjunction with metal type. Like woodcut, wood engraving was a relief printing process, but the method differed in the orientation of the wooden printing block and in the cutting tools applied in carving it. Woodcut had used a plank, cut from the tree in the direction of its growth, so that the grain ran along the printing surface. Wood engraving used a block taken horizontally out of the tree, so that the engraving was cut into the end grain of the wood.

Letterpress from wood engraving. Thomas Nast. That Everlasting Hungry Wail from Harper’s Weekly. October 10, 1885. 14 3/16 x 9 9/16” (36 x 24.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. A two-color wood engraving by an anonymous engraver from a drawing by Nast.

The woodblock had always been cut with a chisel or gouge, woodworking tools with an ancient lineage. The newer wood engraving, cut in end-grain wood, got its name because it was made with a burin, a completely different cutting tool. The burin is small, fits tightly into the hand, and is used horizontally, moving along the wood surface rather than being hammered down into it. At the cutting end there is a lozenge-shaped face, set at an angle, and the lower point of this end is pushed into the surface to make a groove. The burin was probably first developed to do decorative metalwork but is adapted to the cutting of engravings in wood as well. The term “engraving” is connected to the use of this tool; copper engravings, for example, are made with intaglio plates worked with a burin to make grooves in the metal that hold ink. The word “engraving” causes a lot of confusion and we need to remember that it applies to very different sorts of printing.