Intaglio and Planographic Printing

In this segment, taken from his 2008 talk at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for his exhibition The Printed Picture, Richard Benson walks us through the processes of intaglio and planographic printing. He gives an overview of copper engraving, etching, the combination of etching and engraving, steel engraving, aquatint, and mezzotint. Pictures associated with each of the main themes presented in the segment can be found by clicking on any of the fields below.

Intaglio and Planographic Printing Introduction (see Relief Printing)

-

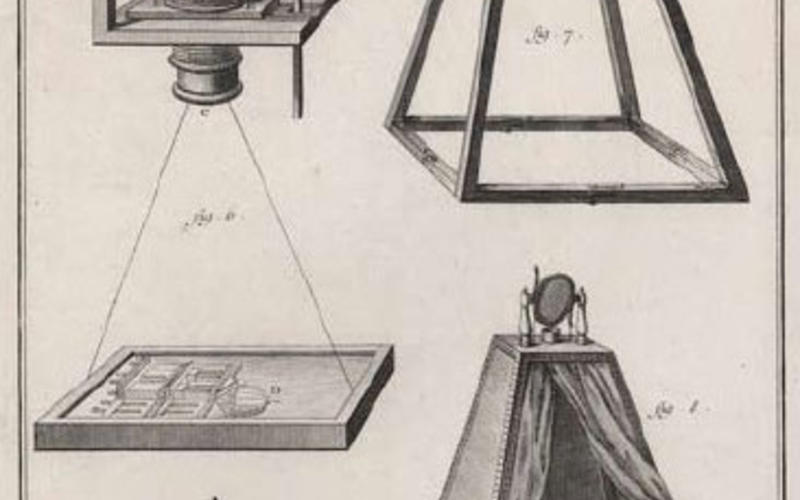

Copper engraving. Jacques-Louis Goussier. Dessin, Chambre Obscure from L’Encyclopédie de Diderot. c. 1772 (Printed by Desehrt). 13¼ x 8 1/4" (33.6 x 21 cm).This section examines two of the great printing processes: intaglio, which means printing from the low part of a printing plate (as opposed to the high parts used in relief printing), and planographic printing, which prints from a material with a smooth surface. The most common intaglio processes are engraving and etching; the best-known of the planographic processes is stone lithography.Copper Engraving

Copper engraving. Jacques-Louis Goussier. Dessin, Chambre Obscure from L’Encyclopédie de Diderot. c. 1772 (Printed by Desehrt). 13¼ x 8 1/4" (33.6 x 21 cm).This section examines two of the great printing processes: intaglio, which means printing from the low part of a printing plate (as opposed to the high parts used in relief printing), and planographic printing, which prints from a material with a smooth surface. The most common intaglio processes are engraving and etching; the best-known of the planographic processes is stone lithography.Copper Engraving

Copper Engraving (00:00 - 04:58)

-

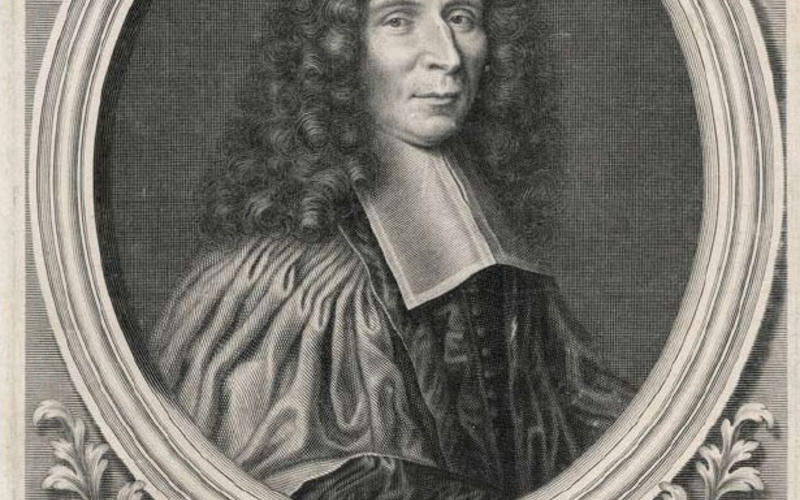

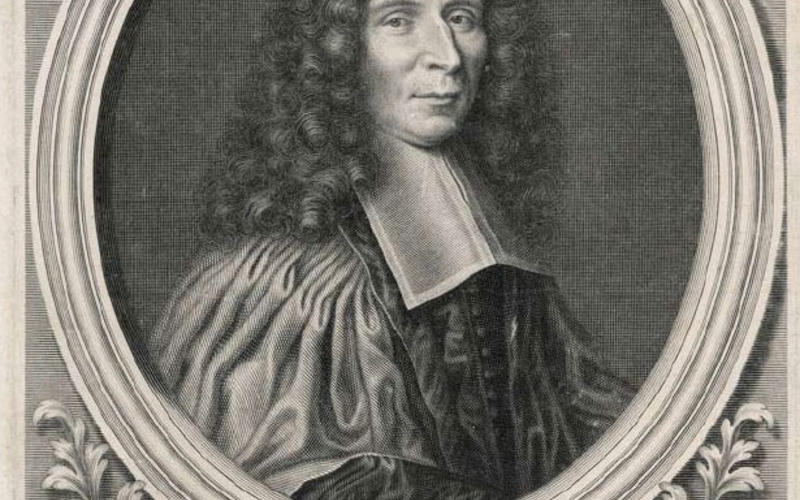

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.With this rather stiff picture of Monsieur Helyot we enter a completely different world from that of wood-based relief prints. The print is a copper engraving that has been printed by the intaglio process. “Intaglio” comes from the Italian “intagliere,” to “cut in” or carve, and describes the class of printing that uses grooves in metal to hold the printing ink. Relief printing, such as the woodcut and the wood engraving, is done by applying ink to the high parts of a printing matrix; intaglio uses the low parts instead. Using a burin, the engraver cuts lines into a polished plate. These lines hold the ink, which the pressure of the printing press transfers to the paper. Engravings were a hugely important pictorial system for centuries, starting to be common in the 1500s and dominating fancy printing until the industrial revolution. Most intaglio printing of this period was done with copper plates.Copper Engraving

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.With this rather stiff picture of Monsieur Helyot we enter a completely different world from that of wood-based relief prints. The print is a copper engraving that has been printed by the intaglio process. “Intaglio” comes from the Italian “intagliere,” to “cut in” or carve, and describes the class of printing that uses grooves in metal to hold the printing ink. Relief printing, such as the woodcut and the wood engraving, is done by applying ink to the high parts of a printing matrix; intaglio uses the low parts instead. Using a burin, the engraver cuts lines into a polished plate. These lines hold the ink, which the pressure of the printing press transfers to the paper. Engravings were a hugely important pictorial system for centuries, starting to be common in the 1500s and dominating fancy printing until the industrial revolution. Most intaglio printing of this period was done with copper plates.Copper Engraving -

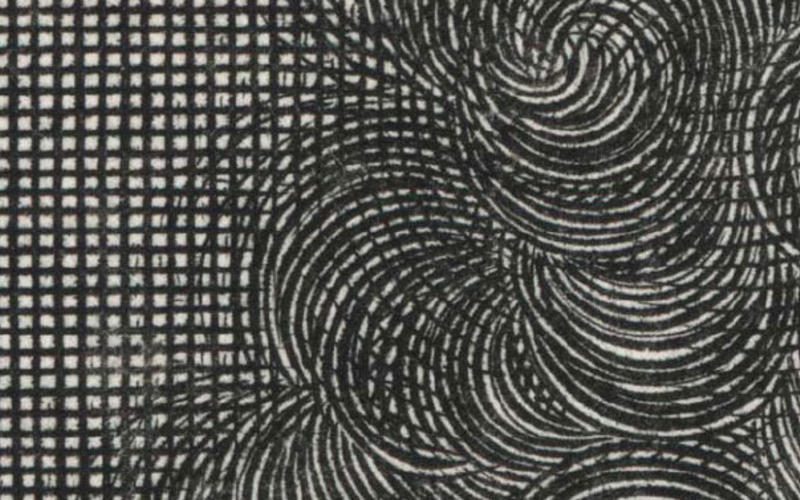

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The curls of Monsieur Helyot’s wig were made by rotating the plate. The square-mesh background was engraved using some sort of straightedge as a guide for the burin.Copper is a tough material to cut with the burin—it is stringy and resists the tool—but when properly handled it can produce precise and delicate plates that last for many impressions. The burin is a small, lightweight thing, and pushing it in a controlled way across the copper surface is very hard. Much engraving was done instead by holding the tool tightly and moving the plate against it; that way the engraver was using both hands together to guide the line. One easy way of doing this was to rest the plate on a leather pad and rotate it. As a result, many old engravings include a lot of smoothly curved lines, making them the perfect medium for describing the fashionable wigs that swell people wore at one time. We see a perfect example of this in Monsieur Helyot’s absurd hair.In the hands of a master, copper engraving could make great pictures, but many are awkward. They were often used to make reproductions of paintings, and in the example here, the lettering and the geometric and floral borders are fine, but the articulated cloth shows signs of a struggle on the engraver’s part; the difficulties of cutting the plate have overcome the descriptive requirements of the picture. The face, on the other hand, is beautifully done. Many of the engravings that have survived in museum and private collections are terrific but a vast number are simply terrible, because of the difficulties of engraving the copper.Detail of Copper Engraving

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The curls of Monsieur Helyot’s wig were made by rotating the plate. The square-mesh background was engraved using some sort of straightedge as a guide for the burin.Copper is a tough material to cut with the burin—it is stringy and resists the tool—but when properly handled it can produce precise and delicate plates that last for many impressions. The burin is a small, lightweight thing, and pushing it in a controlled way across the copper surface is very hard. Much engraving was done instead by holding the tool tightly and moving the plate against it; that way the engraver was using both hands together to guide the line. One easy way of doing this was to rest the plate on a leather pad and rotate it. As a result, many old engravings include a lot of smoothly curved lines, making them the perfect medium for describing the fashionable wigs that swell people wore at one time. We see a perfect example of this in Monsieur Helyot’s absurd hair.In the hands of a master, copper engraving could make great pictures, but many are awkward. They were often used to make reproductions of paintings, and in the example here, the lettering and the geometric and floral borders are fine, but the articulated cloth shows signs of a struggle on the engraver’s part; the difficulties of cutting the plate have overcome the descriptive requirements of the picture. The face, on the other hand, is beautifully done. Many of the engravings that have survived in museum and private collections are terrific but a vast number are simply terrible, because of the difficulties of engraving the copper.Detail of Copper Engraving

Etching (09:08 - 11:07)

-

Etching with aquatint. Adriaen Van Ostade. The Family. 1647. 7 1/8 x 6 1/4" (18.1 x 15.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This impression is a late one, made after the artist’s death. The copper plate from which it was printed was worn, and some aquatint was added to strengthen the image.Etching was a remarkable technical breakthrough in intaglio printing. It had been known for many years that some acids could dissolve metal, and that some waxy materials could be applied to the metal surface to resist the acid and so produce etched designs. This technique had long been used in metalwork having no connection whatever to printing. At some point, probably in the 1500s, the idea of etching through a resist was applied to intaglio printing. The technique itself is simple. If a copper plate (of the same kind used for engraving) is coated with a thin layer of soft wax, an artist can draw through the wax with a sharp needle.Etching with Aquatint

Etching with aquatint. Adriaen Van Ostade. The Family. 1647. 7 1/8 x 6 1/4" (18.1 x 15.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This impression is a late one, made after the artist’s death. The copper plate from which it was printed was worn, and some aquatint was added to strengthen the image.Etching was a remarkable technical breakthrough in intaglio printing. It had been known for many years that some acids could dissolve metal, and that some waxy materials could be applied to the metal surface to resist the acid and so produce etched designs. This technique had long been used in metalwork having no connection whatever to printing. At some point, probably in the 1500s, the idea of etching through a resist was applied to intaglio printing. The technique itself is simple. If a copper plate (of the same kind used for engraving) is coated with a thin layer of soft wax, an artist can draw through the wax with a sharp needle.Etching with Aquatint -

Etching. Johann Hulsman. The Elder and the Maiden. c. 1634 (Printed by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1635). 4 x 4 3/4" (10.2 x 12.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The linear net used to emulate tone in the woodcut shows up in engravings and etchings as delicate cross-hatching.If the plate is then placed in an acid bath, the lines bared by the needle will be etched into it while those areas protected by the wax will remain intact. The etched lines will be rougher than the smooth grooves cut by the burin, but they will hold ink and be printable. Etching transformed intaglio printing. The older method of hand engraving had been a predominantly reproductive medium. It was so hard to do, and required so much skill, that a class of engravers evolved who were not artists but craftsmen concerned only with reproducing the work of painters. Etching allowed artists to apply linear designs to a copper plate themselves, with the same ease with which they might draw on paper.Little pressure was needed to make the needle move freely through the resist. Once a plate was etched and the resist removed, further work could be done on the plate by using the needle to draw with more pressure, raising burrs capable of holding ink. This technique, called “drypoint,” did not require etching, and allowed the artist to do rapid work that could be seen on a proof print without the delay necessitated by an additional etching stage. Etching and drypoint produced prints with a different character from the older, more restrained forms of reproductive copper engraving. Almost as soon as etching was developed, engravers began to use it to help them make their hand-cut plates; many prints combine both methods. In some etchings we'll see the lines have the nervous quality of the hand rather than the stiff appearance of the burin meeting intransigent copper. When engravings were printed, the inked plates were wiped so thoroughly that the background was absolutely clean. When etching came along things became more casual, and sometimes the printer would leave ink on the plate surface, to add to the tonality of the print.Etching

Etching. Johann Hulsman. The Elder and the Maiden. c. 1634 (Printed by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1635). 4 x 4 3/4" (10.2 x 12.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The linear net used to emulate tone in the woodcut shows up in engravings and etchings as delicate cross-hatching.If the plate is then placed in an acid bath, the lines bared by the needle will be etched into it while those areas protected by the wax will remain intact. The etched lines will be rougher than the smooth grooves cut by the burin, but they will hold ink and be printable. Etching transformed intaglio printing. The older method of hand engraving had been a predominantly reproductive medium. It was so hard to do, and required so much skill, that a class of engravers evolved who were not artists but craftsmen concerned only with reproducing the work of painters. Etching allowed artists to apply linear designs to a copper plate themselves, with the same ease with which they might draw on paper.Little pressure was needed to make the needle move freely through the resist. Once a plate was etched and the resist removed, further work could be done on the plate by using the needle to draw with more pressure, raising burrs capable of holding ink. This technique, called “drypoint,” did not require etching, and allowed the artist to do rapid work that could be seen on a proof print without the delay necessitated by an additional etching stage. Etching and drypoint produced prints with a different character from the older, more restrained forms of reproductive copper engraving. Almost as soon as etching was developed, engravers began to use it to help them make their hand-cut plates; many prints combine both methods. In some etchings we'll see the lines have the nervous quality of the hand rather than the stiff appearance of the burin meeting intransigent copper. When engravings were printed, the inked plates were wiped so thoroughly that the background was absolutely clean. When etching came along things became more casual, and sometimes the printer would leave ink on the plate surface, to add to the tonality of the print.Etching

Etching and Engraving (07:07 - 09:23)

-

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.All copper intaglio printing plates had a smooth polished surface into which the engraved or etched lines were incised. The printer would cover the plate completely with a fairly stiff ink, consisting of pigment in oil, and then wipe off the excess ink using a series of heavily starched cloths scrunched into balls. The wiping gradually removed ink from the plate surface, but the ink in the engraved grooves or lines would remain. After wiping with progressively cleaner cloths, the printer would give the plate a final wiping with the palm of his hand, often after lightly dusting the skin with chalk, to remove every trace of ink from the plate surface. Finally the plate was placed face up on the flat bed of a press that had two rigid rollers between which the bed could move.Copper Engraving

Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.All copper intaglio printing plates had a smooth polished surface into which the engraved or etched lines were incised. The printer would cover the plate completely with a fairly stiff ink, consisting of pigment in oil, and then wipe off the excess ink using a series of heavily starched cloths scrunched into balls. The wiping gradually removed ink from the plate surface, but the ink in the engraved grooves or lines would remain. After wiping with progressively cleaner cloths, the printer would give the plate a final wiping with the palm of his hand, often after lightly dusting the skin with chalk, to remove every trace of ink from the plate surface. Finally the plate was placed face up on the flat bed of a press that had two rigid rollers between which the bed could move.Copper Engraving -

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The short strokes begin thin and then broaden as the burin enters the copper. In areas where they portray the desired tone inadequately, the engraver has added small marks between them.A sheet of damp rag-based paper was set on top of the inked plate; two or more layers of thick felt went on top of that; and the bed was passed between the rollers. The press—properly called a mangle—could exert tremendous pressure on the sandwich of plate, paper, and felt. The pressure was so high that the edges of the plate had to have smooth bevels, to avoid cutting the paper and felts. Once through the press, the paper could be pulled off the plate, and the ink held in the grooves would have been transferred to it. If the relationship between ink, paper, and pressure had been right, the printed lines would have a physical height that no other printing process could produce. No mark in printing can compare with a fine intaglio line.Detail of Copper Engraving

Detail of Copper engraving. Nicolas Bazin. Portrait de Monsieur Helyot Conseiller. 1686. 10 1/4 x 7 3/4" (26 x 19.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The short strokes begin thin and then broaden as the burin enters the copper. In areas where they portray the desired tone inadequately, the engraver has added small marks between them.A sheet of damp rag-based paper was set on top of the inked plate; two or more layers of thick felt went on top of that; and the bed was passed between the rollers. The press—properly called a mangle—could exert tremendous pressure on the sandwich of plate, paper, and felt. The pressure was so high that the edges of the plate had to have smooth bevels, to avoid cutting the paper and felts. Once through the press, the paper could be pulled off the plate, and the ink held in the grooves would have been transferred to it. If the relationship between ink, paper, and pressure had been right, the printed lines would have a physical height that no other printing process could produce. No mark in printing can compare with a fine intaglio line.Detail of Copper Engraving

Steel Engraving (19:45 - 21:25)

-

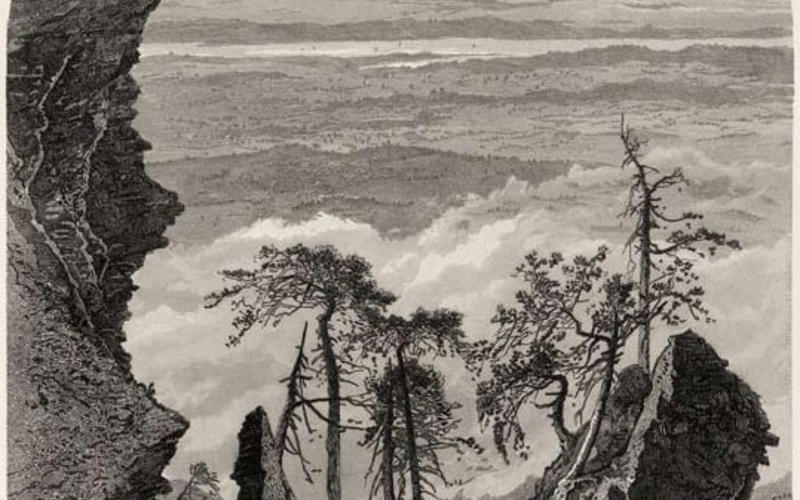

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.Copper printing plates wear out with use. The abrasion of wiping and the pressure of printing can affect the plate quite rapidly: the edges of the incised grooves become rounded and the wiped plate holds less ink, so the print gradually becomes lighter through the successive impressions of an edition. One way to print intaglio in longer editions was to engrave the plates in steel instead of copper. Steel was difficult to work; instead of simply holding the burin by hand, the engraver often had to strike it with a hammer. The problem was compounded by the fact that a steel tool was being used to cut steel, but one characteristic of that material is that it can be prepared soft or hard—the steel burin could be tempered until it could cut the softer plate. Steel plates produced a new class of prints that look very different from those made with copper. They were called “steel engravings,” but a great deal of etching was almost invariably present as well.Steel Engraving

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.Copper printing plates wear out with use. The abrasion of wiping and the pressure of printing can affect the plate quite rapidly: the edges of the incised grooves become rounded and the wiped plate holds less ink, so the print gradually becomes lighter through the successive impressions of an edition. One way to print intaglio in longer editions was to engrave the plates in steel instead of copper. Steel was difficult to work; instead of simply holding the burin by hand, the engraver often had to strike it with a hammer. The problem was compounded by the fact that a steel tool was being used to cut steel, but one characteristic of that material is that it can be prepared soft or hard—the steel burin could be tempered until it could cut the softer plate. Steel plates produced a new class of prints that look very different from those made with copper. They were called “steel engravings,” but a great deal of etching was almost invariably present as well.Steel Engraving -

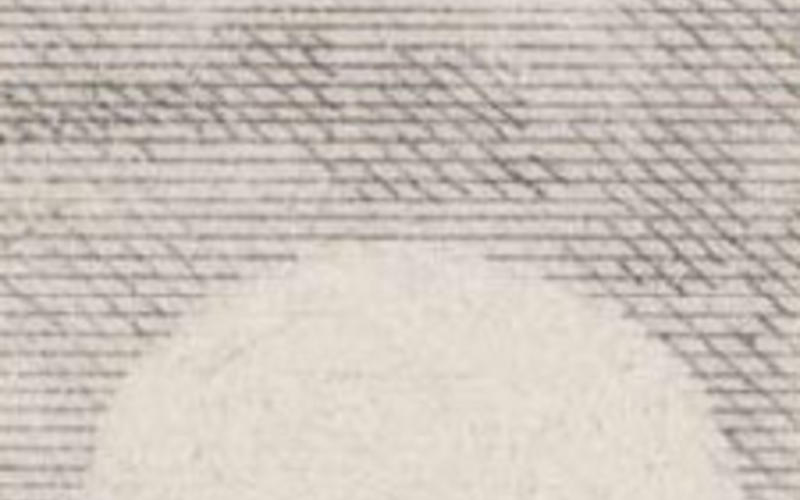

Detail of Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870. (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. In almost all steel engravings that depict a delicate pale sky, the appearance of tone is generated by the use of a burin guided by a straightedge. The two sets of lines in this detail, both made in that way, are angled at approximately thirty degrees to each other. This angle was chosen because overlapping linear designs often create disturbing “moiré” patterns, and printers learned that a thirty-degree difference minimized them.Cuts made with a burin tend to curve in one direction only; a line drawn with an etching needle can freely change direction in a single stroke. These different lines can often indicate whether a print was made by engraving or etching. Almost every piece of steel engraving that I have seen includes a substantial amount of etching, so the process name is somewhat of a misnomer. Steel engravings were very popular in the 1870s and ’80s and often turned up in art books.Detail of Steel Engraving

Detail of Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870. (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. In almost all steel engravings that depict a delicate pale sky, the appearance of tone is generated by the use of a burin guided by a straightedge. The two sets of lines in this detail, both made in that way, are angled at approximately thirty degrees to each other. This angle was chosen because overlapping linear designs often create disturbing “moiré” patterns, and printers learned that a thirty-degree difference minimized them.Cuts made with a burin tend to curve in one direction only; a line drawn with an etching needle can freely change direction in a single stroke. These different lines can often indicate whether a print was made by engraving or etching. Almost every piece of steel engraving that I have seen includes a substantial amount of etching, so the process name is somewhat of a misnomer. Steel engravings were very popular in the 1870s and ’80s and often turned up in art books.Detail of Steel Engraving -

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.The usual practice in these volumes was mostly to use run-of-the-mill illustrations printed from wood engravings locked up with the metal type used for the text. Scattered throughout the book, though, would be lush steel engravings, printed on beautiful thick paper bound into the more humble letterpress signatures. This particular plate is from Picturesque America, a two-volume publication by D. Appleton & Co. Beautiful books like this one are sought out by print dealers who cut out the pages to sell as single prints in antique shops. It is a tragedy that this happens, but I am as bad as they are: the plate we see here is one of a half dozen or so that I cut out of my copy of the book, to use in teaching my graduate students about the pictorial history of ink on paper.Steel Engraving

Steel engraving. Harry Fenn. The Catskills from Picturesque America, Volume II (New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1874). c. 1870 (Printed by S. V. Hunt, 1974). Arched top: 8 7/8 x 5 15/16" (22.6 x 15.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.The usual practice in these volumes was mostly to use run-of-the-mill illustrations printed from wood engravings locked up with the metal type used for the text. Scattered throughout the book, though, would be lush steel engravings, printed on beautiful thick paper bound into the more humble letterpress signatures. This particular plate is from Picturesque America, a two-volume publication by D. Appleton & Co. Beautiful books like this one are sought out by print dealers who cut out the pages to sell as single prints in antique shops. It is a tragedy that this happens, but I am as bad as they are: the plate we see here is one of a half dozen or so that I cut out of my copy of the book, to use in teaching my graduate students about the pictorial history of ink on paper.Steel Engraving

Aquatint (21:25 - 30:39)

-

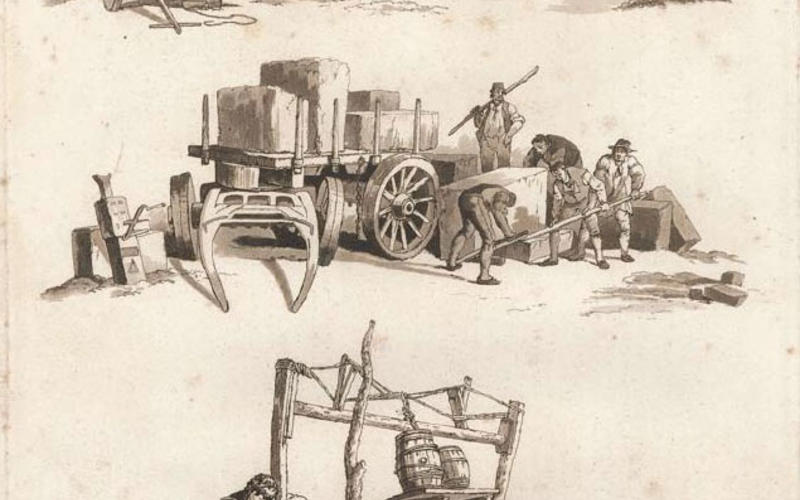

Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823 (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This particular plate was published some years earlier in January 1823. Pyne is given credit for the drawing and etching, and J. Hill is credited for the aquatint.Aquatint is a form of etching. Developed in the eighteenth century, it was the first truly tonal system of ink printing. The cross-hatching used in relief printing and engraving had involved small marks that allowed black ink to appear to the eye as various shades of gray, but that did so by tricking the eye. Aquatint managed this by generating a printing plate with a fine array of cells etched to variable depths, so that the ink was actually put down in different thicknesses. The ink was manufactured so that a thin film looked pale, a thicker one darker, and, when finally thick enough, the deposit appeared black. Aquatint could portray tone in beautiful gradations.Aquatint

Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823 (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This particular plate was published some years earlier in January 1823. Pyne is given credit for the drawing and etching, and J. Hill is credited for the aquatint.Aquatint is a form of etching. Developed in the eighteenth century, it was the first truly tonal system of ink printing. The cross-hatching used in relief printing and engraving had involved small marks that allowed black ink to appear to the eye as various shades of gray, but that did so by tricking the eye. Aquatint managed this by generating a printing plate with a fine array of cells etched to variable depths, so that the ink was actually put down in different thicknesses. The ink was manufactured so that a thin film looked pale, a thicker one darker, and, when finally thick enough, the deposit appeared black. Aquatint could portray tone in beautiful gradations.Aquatint -

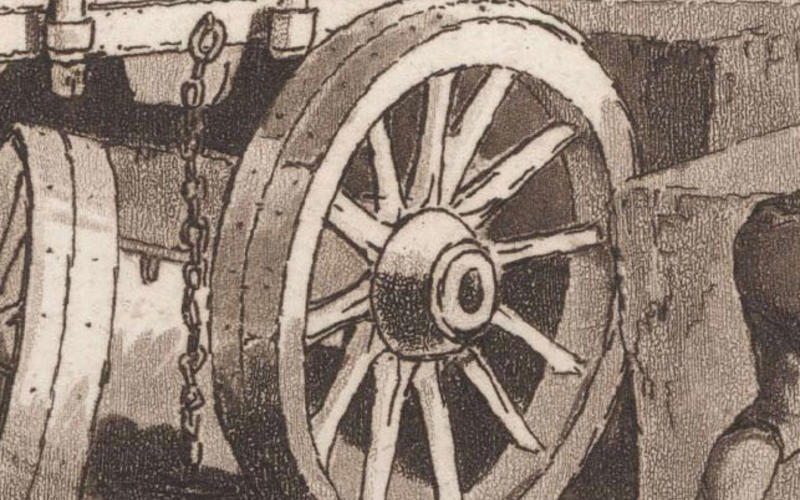

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This detail—an eight-times enlargement of the wheel on the previous page—shows evidence of two aquatints: a fine one, which produced the gray tone in the center of this blowup, and a coarser one, slightly vertical, that managed the rest of the tones. The darkest part, at the bottom of the picture, shows evidence of needle work done through the aquatint to make an even darker tone.It was used for hand-drawn prints in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and then was adapted to photogravure in the 1850s. The basis of an aquatint was a fine deposit of acid-resistant grains—usually asphaltum or rosin—applied in a random pattern to a copper plate.The printer could spread these particles evenly with a device called a “dusting box” or could scatter them onto the plate more irregularly by sifting them through a piece of cloth, traditionally a sock, which could be squeezed or shaken over the plate to put down an aquatint grain in any desired area. Once applied, and set with heat, the particles would resist the etching chemical, protecting the original plate surface during the etch. If they covered more than 50 percent of the plate surface they tended to form a connected network, and the etching took place in the gaps in the net; if the aquatint was light, it was the etched areas that would form a network while the nonetched areas became separate points. In either case the result was a delicate pattern of pockets in the plate—tiny etched areas that could hold ink. After etching, the printer would remove the asphaltum or rosin grains with a solvent. He would ink the plate, then wipe it, and his wiping cloth or hand would run across the higher, nonetched areas without removing the ink from the pockets. If the etching was deep the tone produced would be dark; if the etching was light—only a few seconds or so—the tone would be pale and smooth. Complex pictures such as Pyne and Hill's were made by etching a single aquatint in many discrete steps, each deeper than the one before. To fully understand this we need to examine a magnified section of the plate.Detail from Aquatint

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. This detail—an eight-times enlargement of the wheel on the previous page—shows evidence of two aquatints: a fine one, which produced the gray tone in the center of this blowup, and a coarser one, slightly vertical, that managed the rest of the tones. The darkest part, at the bottom of the picture, shows evidence of needle work done through the aquatint to make an even darker tone.It was used for hand-drawn prints in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and then was adapted to photogravure in the 1850s. The basis of an aquatint was a fine deposit of acid-resistant grains—usually asphaltum or rosin—applied in a random pattern to a copper plate.The printer could spread these particles evenly with a device called a “dusting box” or could scatter them onto the plate more irregularly by sifting them through a piece of cloth, traditionally a sock, which could be squeezed or shaken over the plate to put down an aquatint grain in any desired area. Once applied, and set with heat, the particles would resist the etching chemical, protecting the original plate surface during the etch. If they covered more than 50 percent of the plate surface they tended to form a connected network, and the etching took place in the gaps in the net; if the aquatint was light, it was the etched areas that would form a network while the nonetched areas became separate points. In either case the result was a delicate pattern of pockets in the plate—tiny etched areas that could hold ink. After etching, the printer would remove the asphaltum or rosin grains with a solvent. He would ink the plate, then wipe it, and his wiping cloth or hand would run across the higher, nonetched areas without removing the ink from the pockets. If the etching was deep the tone produced would be dark; if the etching was light—only a few seconds or so—the tone would be pale and smooth. Complex pictures such as Pyne and Hill's were made by etching a single aquatint in many discrete steps, each deeper than the one before. To fully understand this we need to examine a magnified section of the plate.Detail from Aquatint -

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.This four-times enlargement of Pyne and Hill’s print shows the delicate random pattern of the aquatint-generated cells. It also shows that the picture has a simple line-drawn skeleton, an initial drawing into which the tones generated by the aquatint have been fitted. The tones themselves do not gradate smoothly from one value to another but change in discrete steps. I have set small squares of the six visible tonal levels in the print, along with the plain paper base as the lightest step, below the detail. In fact there are eight tones in the picture: the paper, six levels of aquatint, and the dark value of the etched linear drawing. The print was begun as a plain etching—a line drawing made with a needle in a plate.Once it was etched and a trial print or “proof” was made to check the drawing, the plate was cleaned and a superb aquatint was applied over the entire surface. Before any further etching was done, the areas of the picture that were to remain plain, unprinted paper were “staged out” by being painted over with a resist (probably asphaltum dissolved in turpentine). The plate was then given a short acid-bath etch, just enough to lightly etch between the aquatint grains the shallow cells that would produce the lightest printed tone we see—the tone in block 1, one step darker than the bare paper. The plate-maker then shielded the areas that were to retain that tone by painting them with the resist, and the plate was etched again. That bite went to a sufficient depth to produce the tone we see in block 2. And so the procedure continued until the plate had received six etchings, each with different degrees of staging of the plate surface and each to a different depth. Only once these were completed was all of the resist (aquatint particles and staging paint) removed and the plate proofed to see the results. Further corrections were still possible, using etching, drypoint, or even a fresh aquatint, but the bulk of the image was done through the initial linear etching, the single aquatint, and its successive etchings. Aquatint could produce smooth tonal areas with a grain so fine that it was completely invisible to the unaided eye. The process was fairly widely used, most often as a supplement to a conventionally etched picture. The tonal capacity of the aquatint was far greater than a hand-generated print could ever achieve. Photogravure, invented in the 1850s, was the process that harnessed the untapped wonders of the aquatint’s full tonal range.Detail from Aquatint

Detail from Aquatint. W. H. Pyne. Masonry from Picturesque Groups for the Embellishment of Landscape. (London: M.A. Nattali, 1845). c. 1823. (Printed by J. Hill, 1845). 11 1/2 x 9 1/8" (29.2 x 23.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson.This four-times enlargement of Pyne and Hill’s print shows the delicate random pattern of the aquatint-generated cells. It also shows that the picture has a simple line-drawn skeleton, an initial drawing into which the tones generated by the aquatint have been fitted. The tones themselves do not gradate smoothly from one value to another but change in discrete steps. I have set small squares of the six visible tonal levels in the print, along with the plain paper base as the lightest step, below the detail. In fact there are eight tones in the picture: the paper, six levels of aquatint, and the dark value of the etched linear drawing. The print was begun as a plain etching—a line drawing made with a needle in a plate.Once it was etched and a trial print or “proof” was made to check the drawing, the plate was cleaned and a superb aquatint was applied over the entire surface. Before any further etching was done, the areas of the picture that were to remain plain, unprinted paper were “staged out” by being painted over with a resist (probably asphaltum dissolved in turpentine). The plate was then given a short acid-bath etch, just enough to lightly etch between the aquatint grains the shallow cells that would produce the lightest printed tone we see—the tone in block 1, one step darker than the bare paper. The plate-maker then shielded the areas that were to retain that tone by painting them with the resist, and the plate was etched again. That bite went to a sufficient depth to produce the tone we see in block 2. And so the procedure continued until the plate had received six etchings, each with different degrees of staging of the plate surface and each to a different depth. Only once these were completed was all of the resist (aquatint particles and staging paint) removed and the plate proofed to see the results. Further corrections were still possible, using etching, drypoint, or even a fresh aquatint, but the bulk of the image was done through the initial linear etching, the single aquatint, and its successive etchings. Aquatint could produce smooth tonal areas with a grain so fine that it was completely invisible to the unaided eye. The process was fairly widely used, most often as a supplement to a conventionally etched picture. The tonal capacity of the aquatint was far greater than a hand-generated print could ever achieve. Photogravure, invented in the 1850s, was the process that harnessed the untapped wonders of the aquatint’s full tonal range.Detail from Aquatint

Mezzotint (15:12 - 19:45)

-

Mezzotint. After Sir Anthony Van Dyck. King Charles I. c. 1635 (Printed by Isaac Beckett, c. 1685). 13 1/8 x 9 13/16" (33.3 x 25 cm). Collection of John Benson. Beckett’s title, beautifully engraved on the mezzotint plate, is “Charles, by the grace of God King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.”The mezzotint is a strange intaglio process that was developed in the early 1600s. The basis of the process was to cover a plate with ink-holding surface indentations to print a deep, even, black tone, then to polish out some of those serrations to make them print lighter. This variation of light and dark produced the picture. The nickname for mezzotint was “manière noire,” reflecting the fact that the picture was extracted from blackness. The initial plate preparation was done by someone in the print shop—certainly not the artist—and was carried out by roughening the plate surface with a tool called a “rocker,” a chisel-like instrument with a curved cutting edge and with grooves running along the length of the blade.Mezzotint

Mezzotint. After Sir Anthony Van Dyck. King Charles I. c. 1635 (Printed by Isaac Beckett, c. 1685). 13 1/8 x 9 13/16" (33.3 x 25 cm). Collection of John Benson. Beckett’s title, beautifully engraved on the mezzotint plate, is “Charles, by the grace of God King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland.”The mezzotint is a strange intaglio process that was developed in the early 1600s. The basis of the process was to cover a plate with ink-holding surface indentations to print a deep, even, black tone, then to polish out some of those serrations to make them print lighter. This variation of light and dark produced the picture. The nickname for mezzotint was “manière noire,” reflecting the fact that the picture was extracted from blackness. The initial plate preparation was done by someone in the print shop—certainly not the artist—and was carried out by roughening the plate surface with a tool called a “rocker,” a chisel-like instrument with a curved cutting edge and with grooves running along the length of the blade.Mezzotint -

Oil on Canvas. After Sir Anthony Van Dyck. King Charles I. c. 1635. 49 x 39 1/2" (124.5 x 100.3 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London. This detail from a copy of Van Dyck’s painting shows the image that Beckett copied when he made the mezzotint. All direct printing processes, in which the plate transfers ink to the paper in one step, reverse the image. The image on the plate of the mezzotint had the same orientation as the painting; once printed, it was flopped horizontally.When this tool was rocked firmly back and forth on the plate, and gradually moved across it, the plate took on a mixture of indentations and raised burrs across its entire surface. If inked, a plate thus prepared would have printed a smooth black tone. First, though, the artist worked on it with a burnisher, a small handheld tool with a rounded, highly smooth tip. The polished areas of the surface held less ink than the rougher ones and produced the lighter tones of the picture. The process is considered intaglio—printing from the low—but as well as sinking grooves, the rocker raised burrs that probably held just as much ink, making the technique in many ways related to drypoint.However we classify it, mezzotint produced beautiful values and a fundamentally different look from any other kind of print, but the plate was extremely delicate and had to be printed with great care. Mezzotint editions were far smaller than those of engravings or etchings because of this fragility of the plate. It is very hard to make a good picture with an eraser, which is what the artist was doing in burnishing the plate. In many mezzotints, then, the technique dominates the image and the pictures suffer accordingly. The beautiful and eccentric picture of King Charles of England shows the tonality that mezzotint made possible, but also its potential weaknesses: uneven areas of large tone when no detail is present, and a somewhat odd appearance in the lighter values, which comes from the difficulty of knowing just how the burnished plate will carry ink. When mezzotints were just right, though, their beauty was breathtaking and their degree of technical refinement astonishing.Oil on Canvas

Oil on Canvas. After Sir Anthony Van Dyck. King Charles I. c. 1635. 49 x 39 1/2" (124.5 x 100.3 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London. This detail from a copy of Van Dyck’s painting shows the image that Beckett copied when he made the mezzotint. All direct printing processes, in which the plate transfers ink to the paper in one step, reverse the image. The image on the plate of the mezzotint had the same orientation as the painting; once printed, it was flopped horizontally.When this tool was rocked firmly back and forth on the plate, and gradually moved across it, the plate took on a mixture of indentations and raised burrs across its entire surface. If inked, a plate thus prepared would have printed a smooth black tone. First, though, the artist worked on it with a burnisher, a small handheld tool with a rounded, highly smooth tip. The polished areas of the surface held less ink than the rougher ones and produced the lighter tones of the picture. The process is considered intaglio—printing from the low—but as well as sinking grooves, the rocker raised burrs that probably held just as much ink, making the technique in many ways related to drypoint.However we classify it, mezzotint produced beautiful values and a fundamentally different look from any other kind of print, but the plate was extremely delicate and had to be printed with great care. Mezzotint editions were far smaller than those of engravings or etchings because of this fragility of the plate. It is very hard to make a good picture with an eraser, which is what the artist was doing in burnishing the plate. In many mezzotints, then, the technique dominates the image and the pictures suffer accordingly. The beautiful and eccentric picture of King Charles of England shows the tonality that mezzotint made possible, but also its potential weaknesses: uneven areas of large tone when no detail is present, and a somewhat odd appearance in the lighter values, which comes from the difficulty of knowing just how the burnished plate will carry ink. When mezzotints were just right, though, their beauty was breathtaking and their degree of technical refinement astonishing.Oil on Canvas

Monotypes (see Color Printing)

-

Monotype. Christopher Benson. View of Narragansett Bay. 1987. 9 x 11 3/4" (22.9 x 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Christopher Benson.Planographic printing can be done from an evenly smooth-surfaced printing plate with neither raised areas, such as we find in relief printing, nor low ones, as in intaglio printing. The most basic form of planographic printing is the monotype, which can most easily be described as printing from a finger painting done on a copper plate. The press is the same press used for intaglio printing and the plate is the same copper plate used in engraving and etching, because that is the kind of plate we find in printshops that have those presses. No work is done to the plate, though, except to make sure it is polished and to bevel the edges to avoid cutting the paper and felts during printing. If we smear ink on such a plate and run it through the press with dampened paper on top, the ink will transfer onto the paper.It is surprising to find, though, that not all of the ink transfers; quite a lot is left on the plate. With no additional work to it, the plate can be printed again and a much lighter version of the print will appear. Despite the name of the process, then, we do find monotype editions, which the artist can make by repainting the plate after each impression, using the residue left on the plate as a guide for the new work. Every print in a monotype edition is unique, but all are related through the visual foundation maintained by the succession of pale residual ink images that act as guides to the artist doing the printing. This business of ink left on a plate is extremely important, affecting processes as simple as monotype and as complex as modern offset printing. In all print processes the signal conveyed from plate to paper is generated not only by ink applied for the present impression but by residues of ink left from earlier impressions. The plate prints a union of these inks, so it is obvious that the first impression of any plate cannot represent what the plate will do when printed in an edition. This sounds like a minor point, but it is central to the practice of printing in multiple copies. The simple monotype brings to light some of the complexities of printing plates and the manner in which they transfer ink to paper.Monotype

Monotype. Christopher Benson. View of Narragansett Bay. 1987. 9 x 11 3/4" (22.9 x 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Christopher Benson.Planographic printing can be done from an evenly smooth-surfaced printing plate with neither raised areas, such as we find in relief printing, nor low ones, as in intaglio printing. The most basic form of planographic printing is the monotype, which can most easily be described as printing from a finger painting done on a copper plate. The press is the same press used for intaglio printing and the plate is the same copper plate used in engraving and etching, because that is the kind of plate we find in printshops that have those presses. No work is done to the plate, though, except to make sure it is polished and to bevel the edges to avoid cutting the paper and felts during printing. If we smear ink on such a plate and run it through the press with dampened paper on top, the ink will transfer onto the paper.It is surprising to find, though, that not all of the ink transfers; quite a lot is left on the plate. With no additional work to it, the plate can be printed again and a much lighter version of the print will appear. Despite the name of the process, then, we do find monotype editions, which the artist can make by repainting the plate after each impression, using the residue left on the plate as a guide for the new work. Every print in a monotype edition is unique, but all are related through the visual foundation maintained by the succession of pale residual ink images that act as guides to the artist doing the printing. This business of ink left on a plate is extremely important, affecting processes as simple as monotype and as complex as modern offset printing. In all print processes the signal conveyed from plate to paper is generated not only by ink applied for the present impression but by residues of ink left from earlier impressions. The plate prints a union of these inks, so it is obvious that the first impression of any plate cannot represent what the plate will do when printed in an edition. This sounds like a minor point, but it is central to the practice of printing in multiple copies. The simple monotype brings to light some of the complexities of printing plates and the manner in which they transfer ink to paper.Monotype

Stone Lithography (see Relief Printing)

-

Stone lithograph. Artist unknown. Propositions de la Russie. c. 1885. 9 7/16 x 10 7/8" (24 x 27.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The third great class of printing is planographic, which uses a flat surface. Unlike intaglio and relief printing, the printing surface is not incised; instead, imagery is drawn on it then transferred to the paper. The best-known early form of planographic printing is stone lithography, which exploits the incompatibility of oily ink and water on the surface of a limestone block. Because of its ease of use, it was widely employed for inexpensive newspaper cartoons, which the artist typically drew him or herself on the stone that produced the printed edition.Stone Lithograph

Stone lithograph. Artist unknown. Propositions de la Russie. c. 1885. 9 7/16 x 10 7/8" (24 x 27.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson. The third great class of printing is planographic, which uses a flat surface. Unlike intaglio and relief printing, the printing surface is not incised; instead, imagery is drawn on it then transferred to the paper. The best-known early form of planographic printing is stone lithography, which exploits the incompatibility of oily ink and water on the surface of a limestone block. Because of its ease of use, it was widely employed for inexpensive newspaper cartoons, which the artist typically drew him or herself on the stone that produced the printed edition.Stone Lithograph -

Monotype. Christopher Benson. View of Narragansett Bay. 1987. 9 x 11 3/4" (22.9 x 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Christopher Benson.Relief and intaglio printing are both old processes, gradually developed hundreds of years ago, with no identifiable moment of invention. Not so with lithography, which was invented in 1799, by Alois Senefelder, who developed it as a cheaper alternative to other printing methods. The industrial revolution was rooted in the eighteenth century, built on a foundation of scientific and technical work that created the fields of modern engineering, physics, and chemistry.We think of the nineteenth century as a time of iron beams and steam engines, but all that heavy gear grew out of the fledgling understanding of chemistry in the century before. Lithography could only have happened in this context, since it used chemistry, rather than the older chisels and burins, to define printing surfaces.Monotype

Monotype. Christopher Benson. View of Narragansett Bay. 1987. 9 x 11 3/4" (22.9 x 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Richard Benson © Christopher Benson.Relief and intaglio printing are both old processes, gradually developed hundreds of years ago, with no identifiable moment of invention. Not so with lithography, which was invented in 1799, by Alois Senefelder, who developed it as a cheaper alternative to other printing methods. The industrial revolution was rooted in the eighteenth century, built on a foundation of scientific and technical work that created the fields of modern engineering, physics, and chemistry.We think of the nineteenth century as a time of iron beams and steam engines, but all that heavy gear grew out of the fledgling understanding of chemistry in the century before. Lithography could only have happened in this context, since it used chemistry, rather than the older chisels and burins, to define printing surfaces.Monotype